Applied Research Paper

School Outreach for Tobacco Use Prevention

by Costa Ndayisabye, Nzaramba

B.B.A., Independent Institute of Lay Adventists of Kigali Rwanda, 2009

Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Master’s Degree in Public Health

Concordia University

May 2016

Introduction to the Study

All over the world, public health is continuously experiencing challenges related to tobacco use behaviors among adolescents. Understanding the major causes of these behaviors can give a clue to significantly promote anti-tobacco use campaigns among youth. This research used existing published evidence that focuses on peer relationships and tobacco use in school environments to analyze their correlation and possible prevention strategies.

Problem Statement

It is unquestionably true that tobacco use is still the leading cause of premature deaths in the world. Cigarette smoking damages important numbers of organs in the human body causing both the smoker and people who are exposed to secondhand smoke to be susceptible to diseases. According to the World Health Organization, six million people are killed every year in the world due to tobacco use related illnesses. Half of the people who used tobacco products die from illnesses relating to smoking (WHO, 2015). Research findings indicated that there are a substantial number of smokers who do not experience the common health risks related to tobacco use behaviors (WHO, 2015).

In the United States, 480,000 people die as a result of smoking every year, bringing tobacco use to 1 in 5 of the cause of deaths in the country (CDC, 2015). Many of those who smoke today began smoking when they were young (adolescents). There is a significant prevalence of conventional and non-conventional tobacco use among adolescents. Statistics revealed that 3,800 adolescents smoke their first cigarette every day in the U.S. (CDC, 2015). According to the article “Youth and Tobacco Use” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) if the current smoking prevalence among youth continues 5.6 million of American younger than 18 years old will prematurely die from diseases related to tobacco use, which is equivalent to one of every 13 adolescents.

Although peer relationships are considered to be normal and can sometimes be positive, there is much research that indicated the correlation between peer relationships to the adoption of unhealthy behaviors. According to Forman, “Peer influence is one of the primary contextual factors contributing to adolescent risky behavior” (American Psychological Association, 2015).

Purpose Statement

Understanding the implication of peer relationships in promoting tobacco use prevention campaigns among adolescents in the school environment is the primary goal of this research.

Research Questions and Associated Hypotheses

Question1: Are peer relationships major influential factors of adolescent tobacco use behaviors in school environments?

Null Hypothesis: Peer relationships in school environments are not strong enough to influence adolescent tobacco use behaviors.

Alternative Hypothesis: Peer relationships in school environments are significant catalysts of adolescent behaviors.

Question2: How important are positive peer relationships in promoting tobacco use prevention programs among adolescents in school environments?

Null Hypothesis: Positive peer relationships are not strong strategies to promote tobacco use prevention programs among adolescents in school environments.

Alternative Hypothesis: Positive peer relationships are strong strategies to promote tobacco use prevention programs among adolescents in school environments.

Potential Significance

There is a substantial amount of research that focused on tobacco use behavior among adolescents. Conversely, there are extensive published studies on the impact of social networks on adolescents’ behavior. However, it is important to assess the connectivity of peer relationships among adolescents and the adoption or cessation smoking behavior in school environments. This research therefore, will select the most applicable evidence to systematically answer the above-mentioned questions.

Search Strategy

Electronic searches from Concordia University of Nebraska Library, MEDLINE, CDC, WHO, DHHS and peer reviews from PubMed, Google Scholar and Cochrane database were reviewed to extract important evidence for this study. This study considered two major primary key words: peer relationships in school environments and tobacco use among adolescents in school environments.

Theoretical Foundation

Ecological Systems Theory

Theoretical understanding on why adolescents adopt smoking behavior is an important process that was considered in this study. Although the American psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner initially developed the ecological systems theory to broadly understand factors that influence a child from a microsystem to macrosystem levels, the model has been used by public health professionals to theorize the motive behind individuals’ behavior. One idea of the ecological systems theory is that the environment provides significant influences on individuals’ behavior. Microsystem, Mesosytem, Exosystem and Macrosystem are the four important levels of influence that the ecological systems theory uses to understand environmental impact on individual behavior. It should be noted though that, “some environments foster more risk behaviors than the others” (DiClemente, Salazar, & Crosby, 2013). Wiium and Wold (2009) used the ecological systems theory to assess the impact of the ecological factors on impact on adolescent smoking behavior. The study findings stated that leisure factors, school, and family play significant roles in adolescents’ smoking behavior. Therefore, this research indicates that the ecological systems theory is of utmost importance in examining the effect of peer relationships in school environments in order to plan for strategic tobacco use prevention programs (School Outreach in Tobacco Use Prevention).

Literature Review

Other than home, adolescents spend most of their time in school environments. Adolescents view friendship as an integral part of their daily life, and among themselves, they share ideas, jokes, and other influential factors such as doing homework together, smoking, using drugs, etc. According to the report Developmental Milestone published by the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2015), adolescents between ages 15 and17 years old would prefer to spend more time with their peers than with their parents. Many studies have proven that social networks in schools have a significant influence among students. Though tobacco use is still considered as the leading cause of preventable deaths, substantial numbers of adolescents who use both smoke and smokeless tobacco products learn this behavior from their peers. Research titled Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students (Appendix 2) published by the CDC indicated that there was no prevalent decrease of tobacco use among middle and high school students in the period of 2008 and 2009 (2010). Environments such as school settings have significant impact on tobacco use among adolescents. Research findings stated that adolescents like to have reciprocal relationships with mutual respect and to grow friendship settings by being “friends’ friends” (Mercken, Snijders, Steglich & Hein de Vries, 2009). The study The Social Context of Adolescent Smoking: A Systems Perspective showed that an adolescent who smoked tended to engage in the same behavior with his or her friends (Lakon, Hipp and Timberlake, 2010). Sharing behavioral ideas is an important characteristic among adolescents. Although there is no scientific proof that shows why adolescent friendship is a determinant of smoking behavior, substantial number of reviews considered in this study indicated that there is a certain level at which peer relationships do, indeed, influence the adoption of smoking behavior among adolescents. Consequently, there is a strong likelihood that a friend of an adolescent who smokes will begin smoking as well. However, while peer relations can be considered as factors in promoting risk behaviors, they can also be a platform to market positive behavioral change.

Research Methods

Approach and Design

This study reviewed the existing research relating to the influence of peer relationships among adolescents in school environments, particularly on tobacco use; consequently, the qualitative method was used to collect significant data to answer the question “How important are positive peer relationships in promoting tobacco use prevention programs among adolescents in school environments?” According to Jeanfreau and Jack (2010), qualitative research is an action that focuses on human life experience through a methodical and interactive approach. It was under this perspective that this research collected data to assess possible answers that will support hypotheses. Some findings used to support the hypothesis: “Peer relationships in school environments are significant catalysts of adolescent behaviors,” were quantitative as they refer to provided statistical representations. The systematic review utilized both retrospective correlational designs to collect data. Retrospective design was used because data were extracted from the already published research. The study design is correlational because it predicts the effectiveness of peer relationships to promote tobacco use prevention among adolescents in school environments.

Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

Key search words used to select papers of interest were: (a) tobacco use among adolescents, (b) impact of peer relations in school environments, and (c) social network influence in school environments. Using key search words identified in the background literature review, selected research titles, abstracts and full text were reviewed, and all studies that involved the following criteria: (a) studies published in English presenting factors related to peer relationships or tobacco use among middle and high school adolescents between ages 12 and 19 years old, (c) reported a measure of potential factors that discussed the association between adolescents’ networks and tobacco use in school environments. The reason the study limits the students’ age range to those between middle school and high school students is to exclude all articles that did not conform to the research problem and to specifically find articles that would answer the research questions. Moreover, articles published before 2010 were not considered in order to avoid outdated information. Studies that did not reflect issues related to tobacco use among adolescents were also excluded. However, through critical analysis, reports from the CDC and WHO that provided quantitative information about tobacco risks to health and the impact of peer relationships were included.

Papers that were not qualitatively original were excluded from review. The table below (Table 1) shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to obtain the most significant reviews for the study.

Table 1

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

| · English language papers | · Papers published in other languages | |

| · Effects of peer relationships among adolescents in schools | · Effects of parents on adolescents behavior | |

| · Tobacco use among adolescents aged between ≥12 ≤ 19 years old | · Adults >19 years old and children who are <12 years old | |

| · Papers published ≥ 2010 | · All other papers published before 2010 |

Quality Methodological Assessment

Identified studies that fulfilled the above criteria were critically analyzed for quality before final consideration. Sources of information and search database used in this research are provided in the Appendix A. The student performed data assessment follows procedures provided by Bui (2014) whereby identified papers are arranged according to the two key words of this study previously discussed (p. 66).

Data Analysis Plan

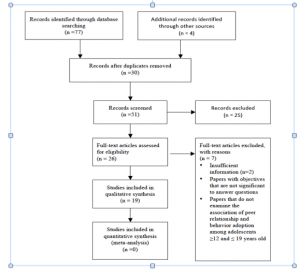

This research uses PRISMA flow diagram to describe the included and excluded studies as and were illustrated in Figure 1. The figure provides the initial number of studies identified and final included papers.

Figure 1

Systematic Search Results Flow Diagram of Included and Excluded Studies

Results

Like other unhealthy behaviors, the soaring number of adolescents with tobacco use problems is becoming critical, especially in school environments. Adolescents spend a considerable amount of time in school with the goal of acquiring new skills. However, the school experience introduces children to different aspects of life. When children start their middle school education, they become much more attached to their peers as friendships are formed from shared experiences and/or common interests. Consequently, peer relationships constitute factors that often result in changes in adolescents’ life styles. This section will present the correlation between tobacco use behaviors and peer relationships among adolescents in school environments. Furthermore, this section will reveal possible strategies to promote tobacco use prevention in school environments using positive peer relationships will be presented. The researcher endeavored to limit research to adolescents who were in middle school and high school. To ensure a systematic representation of evidence in this section, the researcher categorized and summarized the themes.

Data Collection

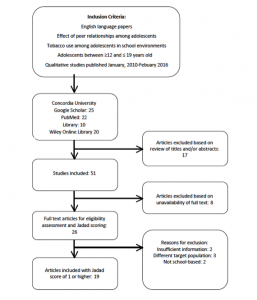

Data represented were completed using database searches and Internet-based sources with respect to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. There were 81 papers identified through the systematic literature reviews in this study. The majority of research selected, analyzed, and employed for this project were transversal studies in nature that were conducted within the last five years. After exclusion of the duplicates, 17 papers were removed based on titles and abstracts that did not reflect the research problems. These included studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Out of 26 full-text analyzed papers, seven articles were excluded for insufficient information or did not reflect the study’s target population and area. Nineteen papers were, therefore, included in the final review (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Studies Inclusion Process for Systematic Review

Data Analysis

Most of the evidence included in this study is cross-sectional in nature. The author selected studies based on the data they contained. With respect to the study questions and the hypotheses for this project and in order to minimize potential bias, the systematic review assessed papers published between January 2010 and February 2016 with targeted populations that are equal to twelve years old and not over nineteen years old. The concise description of included studies, their designs, interventions, populations of interest and primary outcomes are depicted in Table 2 and Table 3 as they relate to the influence of peer relationships among adolescents and tobacco use among adolescents respectively.

Table 1 briefly describes studies included that focused primarily on the effect of peer relationships in school environments and respects all the inclusion criteria of this project. Table 2 briefly presents the analysis of studies included with a main focus of “Tobacco Use Behaviors” among the adolescents. The inclusion criteria presented in the methods section of this study was highly considered.

| Authors | Setting | Study Design | Population and Number (if defined) | Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Score |

| Karakos (2014) | School based analysis | Qualitative interview | High school staff members | Role of peers among adolescents in high schools | Presence of both positive peer support and negative peer influence

Added a space here |

8 |

| Prinstein et al.

(2011) |

School based analysis | Qualitative interview | 43 white adolescents, 11th grade | Susceptibility to peer influence | Normal distributed variable |

8 |

|

Jeon & Goodson (2015) |

Matrix methods: Systematic review |

Adolescents |

Friendship networks and health risk behaviors |

Understanding risky behaviors can be useful to promote health programs |

7 |

|

| Tucker et al. (2014) | School based | Longitudinal study review | Adolescents in 11th and 12th grades | Peer influence and marijuana use | Peer influence on youth acts in different ways

|

6 |

| Marks et al. (2015) | School based | Cross sectional study | 310 students, aged 11-13 years

|

Friendship network characteristics are associated with physical activity and sedentary behavior in early adolescence | Friendships are associated with behaviors |

6 |

| Sussman & Grigsby (2014) | School based | A systematic, exhaustive literature search

|

Students | Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug misuse prevention and cessation programming for alternative high school youth | Successful efforts have focused on instruction in motivation enhancement, life coping skills, and decision-making. |

7 |

Table 1: Characteristics of Included Studies: Peer Relationships’ Influences

| Authors | Setting | Study Design | Population | Intervention | Primary Outcomes | Score |

| Morton and Farhat (2010) | Home and schools | Systematic review | Adolescents | Peer group influences and substance abuse | Adolescents with friends who smoke are likely to smoke

|

8 |

| Green et al. (2013) | In-home survey | Longitudinal survey | Adolescents in 11th and 12th grades (20,745) | Adolescent smoking behavior | Smoking status might be derived from social network |

7 |

| CDC (2013) | School based | Cross-sectional | (24,658) Middle school students (6th & 8th grades) | Tobacco product used in middle schools and high schools | Ethnicity is a major determinant in smoking behavior |

7 |

| Cho, J., Shin, E. & Moon, SS. (2011) | Community | Hierarchical logistic regression analysis | 4,341

Students |

Electronic cigarette smoking among adolescents | Results were statistically significant predictors of e-cigarette experience

|

8 |

| Thomas et al. (2013) | School based | Systematic review | 428,293 students, aged 5-18 years old in 134 studies | Smoking intervention programs in schools | None of the studies showed the effectiveness of the program |

6 |

| Brinn et al. (2012) | Cochrane Review | Youth | Media and smoking cessation | No significant proof for media effect on smoking cessation |

6 |

|

|

Table continues |

|

Table 2: Characteristics of Included Studies: Tobacco Use

| Thomas et al. (2015) | School and community based | Randomized controlled trials | Adolescents | Family based smoking prevention among children | Family based intervention has positive effect on smoking prevention among children |

7 |

| Wakefiled et al. (2014) | Systematic review | Youth | Role of media and youth smoking behaviors | High quality evidence shows the effects of smoking behavior among youth |

6 |

|

| Stanton &

Grimshaw (2013)

|

Community based | Review of randomized controlled trials | Teenagers | Tobacco cessation intervention | No specific intervention strategies on tobacco cessation among teenagers |

6 |

|

Khrosravi et al. (2015) |

School based |

Cross-sectional study |

450 males high school students |

Smoking factors among youth in Iran |

High prevalence of smoking behaviors

|

6 |

| Warren et al. (2015) | School based | Systematic Reviews | 513, 909 students

|

Disparity smoking effects among students from rural and urban schools | Consistent and fair differences of smoking behaviors between rural and urban students |

7 |

| McIsaac et al. (2016) | School based | Scoping review | Youth | Support system level of health promotion in schools (HPS) | Existing policies are challenges for HPS |

6 |

| Sarin et al. (2014) | School based | Cross-sectional anonymous survey | Adolescents | E-cigarette use among middle schools and high schools students | E-cigarette use among adolescents and establishment of policies to limit access are imperatively needed. |

6 |

Fifteen of the nineteen studies included for the final review were conducted in the United States while the four other papers were conducted in South Korea, Iran, Senegal and Australia. The majority of the studies involved children who are in the adolescent age range. While others included children from the ages of five to nineteen. Four studies discussed both peer influence and tobacco use behaviors only among adolescents. They analyzed the correlation between peer influence and the adoption of tobacco use behaviors. Three studies examined the effect of peer relationships, nine discussed tobacco use behaviors and three focused on tobacco prevention. It is important to note that all studies had school environments as their primary area of interest.

Quality Assessment

To minimize potential risks of bias, quality of evidence was also assessed using the traditional Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework (Table 4) that justified the scoring method used in Table 3. Nine papers were considered to contain sufficiently high quality, significant data to answer the research problem (n=9, score=2). Five papers were considered to be of moderate quality with reasonable data (n=5, score=3) while five papers reflected low quality with one or two sections including significant information for the study (n=5, score=1). In all studies (n=19) included in the final review, the author did not find papers with a very low quality grade.

Table 3: Included studies rating using GRADE framework

| Measure | Justification |

| High Quality (9) | Very confident that papers contained relevant information for the study

|

| Moderate Quality (5) | Moderately confident that papers contained relevant information for the study

|

| Low Quality (5) | Mixed findings. Confidence is limited in some part of the papers. Only a few sections of the papers provided important information for the study

|

| Very Low Quality (0) | N/A

|

Even though the nineteen papers which were found to have significant elements needed by the author for this project, consideration may be given to some peer reviews or papers with relevant information for the study and may possibly be published during the compilation of this systematic review. For example, “Tobacco Use Trend Among the Adolescents in the U.S.” which was published in March 2016 would, therefore, be included in the data collection of the result sections.

The nineteen papers considered in this systematic review provided cases with different findings regarding peer relationships and adolescents’ behaviors particularly in the context of tobacco use. The most significant findings are represented in Figure 3. The first column represents studies that pointed to the effect of peer relationships on adolescents’ smoking behaviors whereas the second column specifies authors with different findings.

Figure 3: Findings with similar and different line of findings

| Similar | Different |

| · Adolescent with friend who smokes is likely to smoke (Mortona & Farhat 2010).

· Adolescents’ friendship promotes both negative and positive behavior (Karakos, 2014) · Friendship is associated with behavior (Marks et al.2015) · Smoking behavior might derive from social network (Green et al. 2013) |

· Ethnicity plays a big role in smoking behavior (CDC, 2013).

· Geographic area is the cause of smoking behavior (Warren et al. 2015)

|

Discussion

The study “School Outreach for Tobacco Use Prevention” is a systematic review, which was developed to determine if there is a possible correlation between peer relationships and adolescent smoking behaviors in school environments. Furthermore, the author sought to reveal whether or not peer relationships among adolescents could be used as a channel to promote tobacco cessation programs in school environments.

The use of systematic review in this study addressed significant limitations by comparing the evidence from various prior literature regarding the effect of peer relationships in on tobacco use among adolescents.

Because tobacco use behavior is becoming increasingly common among adolescents, understanding the major causes of this health risk behavior is essential in order to craft appropriate intervention programs.

Besides spending time at home, the majority of adolescents spend a substantial amount of time in school environments. The main purpose of education is to provide vital learning resources to build students’ academic development, physical and mental health statuses. However, when at school, adolescents tend to broaden the academic development purpose to include friendship creation, which encompasses different types of behaviors. While the majority of the studies focus on academic, physical and mental development, the author of this study concentrates his attention on behavioral factors that are derived from peer relationships in school environments, particularly on tobacco use among adolescents. Therefore, school environments are very conducive to understanding the relationship between adolescent friendships and tobacco use behaviors. To deeply understand adolescent behaviors in school environments, the author analytically reviewed various papers that addressed the issue.

Data Interpretation

To better interpret the results in this study, the author categorized the findings into three subjects: (a) “peer relationships among adolescents,” (b) “tobacco use behavior among adolescents,” (c) the correlation of the previously two mentioned categories.

Peer Relationships

The setting of socialization provides opportunities for group interaction. Simply stated, creating friendships is a natural structure for social interaction. Friendship formation varies depending on age, sex, culture, and religion and people adhere to a social group that is compatible with their personal interests. Places such as home, school, church, and the workplace are settings that play a significant role in accommodating social groups. One study found that people from different demographic settings were often influenced by friendships that were consistent with what their peers offered (Morton & Farhat, 2010).

This particular study focused on social networks that involved adolescents, especially in school environments. During the period of adolescence, an individual typically experiences physical changes that are distinctive according to mental and social developmental norms of the specific age group. Peer relationships constitute one of the most important influences on life styles during adolescence. Adolescents tend to have less connection with their parents than they did in their younger years; rather, they are likely to find those who are the same age as them at school to be more important than their parents. The friendships created in school environments open the window to adolescents for both positive and negative behaviors. It is essential to an adolescent to have peer with whom he or she can share ideas and create companionship. According to the article Friendships — Helping Your Child Through Early Adolescence published by the U.S. Department of Education, friendships are important to teenagers’ development. Adolescents who are unsuccessful in making friendships can struggle with “self-esteem” issues and even perform poorly in school (2013). The same article indicated that adolescents consider friendships as a crucial sign of who they are and which direction of life they are taking (U.S.DE, 2013).

In a study conducted by Karakos (2014) regarding the role of peers among adolescents, peer relationships have both positive influences, which were considered as “peer support,” and negative influences. Positive behaviors derive from adolescents’ friendships help adolescents to build confidence and to provide support to themselves in times of stress. Negative behaviors obtained during youth are common and sometimes pose risks to adolescents’ lives, which could lead to problems such as delinquency, health issues and less interest in school. Supporting Karakos findings, two of the papers reviewed in this study indicated that peer relationships had have more influence on adolescents’ behaviors while four papers mentioned that adolescents’ peer relationships are significant to understand risky behaviors. Morton and Farhat (2010) pointed out that the chance of juveniles being susceptible to peer influences is greater, especially in school environments.

Tobacco Use Behavior

Tobacco use is still the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States. A report from the CDC indicated that 16 million Americans suffer from diseases derived from tobacco use whereby 480,000 deaths occurred every year as result of smoking behavior (CDC, 2016). Smoking is found to be responsible for lung diseases, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, stroke, heart disease, and it also increases the risk for tuberculosis (CDC, 2016).

Adolescents constitute the first generation of smoking groups. Research has shown that nearly 90% of individuals who smoke for the first time are adolescents who are 18 years or younger (Park, S., 2011). With that said, tobacco use behavior among adolescents is regarded as an evolving trend that is causing significant challenges to public health. In 2014 a soaring number of adolescents who smoke was recorded, the highest ever in history (U.S.DHHS, 2016). In the United States for example, a report indicated that every day 3,200 people aged 18 years old or younger smoke their first cigarette, which is equivalent to 1,152,000 per year (CDC, 2016). Adolescents who use tobacco experience early health consequences that interfere with the body system and are likely to develop a dysfunction of the peripheral airway and experience a decrease of the forced expiratory in seconds (FEV1) (Park, S., 2011).

Smoking behavior is a learned process that adolescents acquire gradually. Adolescents who use tobacco products tend to use them over and over. The frequency of smoking behavior increases with the length of the smoking period. According to Park (2011), cigarettes were categorized as one of the most addictive products available to consumers. Considering the growing number of adolescents who use tobacco products, it is important to understand the root cause of this health risk to plan for precautionary measures.

Peer Relationships and Tobacco

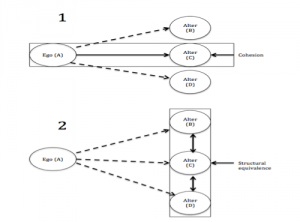

Peer relationships are among the most influential social factors associated with tobacco use among adolescents (Morton & Farhat, 2010). Papers included in this research in one way or the other indicated that adolescents smoking behavior is linked to social network motives. Out of the 19 papers reviewed for the purpose of this study, the author found 13 papers indicating that the role of peer relationships represent a significant influence to risk behaviors including tobacco use among adolescents. Chan and Goodson (2015) stated that adolescents with direct relationships have cohesive behaviors (Figure 4, A-B).

Figure 4: Cohesion and structural equivalence of peer relationships

Adapted from Peer, J. article published by Chan and Goodson (2015).

Figure 4, Part 1 Cohesion represents the diagrams of cohesion and structural equivalence in a network. The significance derived from A and B indicates that there is a strong relationship explaining the existence of cohesion between two teenagers with a direct friendship; conversely, A-B and A-D seem to have indirect relationships indicating the absence of cohesion that might lead to friendships’ influence. Part 2 represents B-C and C-D to be structurally equivalent because adolescents have the same interests, in which case relationships are likely to influence behaviors.

According to Green et al (2012), numerous studies have proven that peer relationships have a significant influence on adolescent smoking behavior. The authors added that adolescents whose peers place a high value on using tobacco products would ultimately tend to emulate the same values for like behavior. The stronger the friendship, the more it builds trust among peers on different behaviors offered mutually. A one-year longitudinal data gathering from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health Tucker et al (2014) indicated that adolescents might feel comfortable in offering illegal substances to their friends or in trying whatever is offered to them by their friends in order to credit their friendships.

Theoretical Interpretation

Studies included in this research did not fully explain the correlation between the influence of peer relationships and tobacco use behavior among adolescents. However, theories indicated that adolescents learn different behaviors including smoking from their peers. Green et al. (2012) presented strong theories that connected peer relationships to adolescent behavior.

Conclusion

Despite of policies in place to restrict smoking in public areas, tobacco remains legal in many countries albeit its incessant hazard to consumers’ health. The use of multiple tobacco products today is predominant among adolescents. This research, therefore, endeavors to analyze possible channels used by youth to adopt tobacco use behavior and identify potential strategies to eradicate smoking habits among adolescents. However, limitations were encountered in this study, which is why the researcher provided recommendations to obtain more evidence that will more clearly determine the major cause of tobacco use among youth and potential prevention strategies.

Limitations

This project has a number of limitations derived from included studies. Based on the Traditional Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE), the author has concluded that five out of the 19 included studies were of low quality due to limited data they contained. Conversely, six studies were inferior in providing significant evidence as they were conducted outside of school environments.

For example, the survey conducted by Tucker et al. (2013) was an in-home based study, which did not discuss important information on adolescent behaviors that might occur in school environments.

When searching for research to include in this study, the author obtained a substantial number of articles that discuss either tobacco use behavior among adolescents or the effects of peer relationships on adolescent behavior. With that being said, most of the studies did not directly discuss the relationship between the two dependent variables of this study (peer relationships and tobacco use behavior), which in turn, led to inadequate findings to support the study’s goal to determine potential correlation between the two behaviors previously mentioned.

Papers included in this study were primarily conducted in different countries, which could lead to cultural differences. These limitations explain disproportionalities in the cross papers included in this study. Additionally, the presence of item bias included cultural-based papers was likely to be present. It is essential to note that poor choices of “cultural phrases” or inadequately assessed cultural items are considered as item bias (Study.com, 2016). Consequently, cultural differences should also be considered as behaviors of students from one school environment could differ from the other.

Unlike experimental studies which apply statistical findings, research based on reviewing the existing articles may have potential biases. The number of findings considered for this systematic review may contain risk of bias, as they could not be independently verified due to the fact that they were self-reported data in nature.

Recommendations

Tobacco use behavior among adolescents is an alarming public health challenge today. Finding appropriate causes that lead to this unhealthy behavior can be crucial in determining strategies to prevent adolescents from using tobacco. Unfortunately, the author did not find specific studies that described the root cause of this unsafe behavior. As a consequence, the number of adolescents using tobacco products is soaring tremendously.

Although comparing results from different sources is an appropriate method when conducting a systematic review (Barrat & Kirwan, 2009), this study does not fully justify that peer relationships among adolescents are strategic channels to promote tobacco use prevention in school environments. Furthermore, the author did not find evidence that described the correlation between tobacco use behavior and peer relationships among adolescents in school environments. Thus, promotion of tobacco use cessation programs should be critically assessed before actual implementation.

Findings from this study suggested that further research is needed regarding the impact of peer influence as it relates to adolescent tobacco use behavior in school environments. Schools and school personnel play a vital role in promoting students’ overall health; therefore, research which focuses on tobacco use among adolescents should consider school staff as participants in the effort of preventing this harmful behavior.

As a global issue, adolescent tobacco use has far-reaching effects as it can have a significant positive impact on the health of current and future generations. If governments and health professionals around the world are willing to work with stakeholders in considering and addressing the seriousness and magnitude of this issue, support studies designed to provide a clear understanding of the motivation for adolescents to use tobacco, and join in the effort of combating and eradicating tobacco use, especially in school environments, a significant reduction of this health risks within citizens would be the likely result. On the other hand, if the necessary efforts are not put forth society will continue to be placed at risk for myriad health problems for generations to come.

References

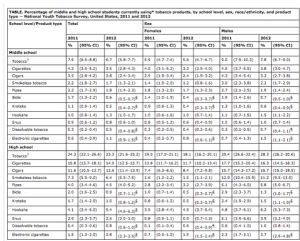

Appendix B: Percentage of middle and high school students currently using tobacco products, by school level, sex, race/ethnicity, and product type — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2011 and 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6245a2.htm

Barrat H., & Kirwan, M. (2009). Systematic reviews, methods for combining data from several studies, and meta-analysis. Retrieved from

http://www.healthknowledge.org.uk /public-health-textbook/research-methods/1a-epidemiology/systematic-reviews-methods-combining-data

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2016). Smoking and tobacco use. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Developmental milestone. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/adolescence2.html

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2015). Health effects of cigarette smoking. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). Youth and tobacco use. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2013). Youth and tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/youth_data/tobacco_use/

Centers from Disease Control and Prevention (2010). Tobacco use among middle and high school students. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6245a2.htm

DiClemente, R.J., Salazar, L.F., & Crosby, R.A. (2013). Health behavior theory for public health. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Forman, A. A. (2015). Facets of peer relationships and their associations with adolescent risk-taking behavior. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2015/12/adolescent-risk-taking.aspx

Jeanfrau, S. and Jack, L. (2010) Appraising qualitative research in health education: Guidelines for public health educators. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3012622/

Lakon, C., Hipp, J., & Timberlake, D. (2010). The social context of adolescent smoking: A systems perspective. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882398/

Mercken, L., Snijders, T., Steglich, C. & Hein de Vries, A. (2009). Dynamics of adolescent friendship networks and smoking behavior: Social network analyses in six European countries. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi= 10.1.1.663.8121&rep=rep1&type=pdf type=pdf

Study.com (2016). Testing bias, cultural bias and language differences in assessments. Retrieved from http://study.com/academy/lesson/testing-bias-cultural-bias-language-differences-in-assessments.html

Sussman, S. Arriaza, B. & Grigsby, T. (2014). Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug misuse prevention and cessation programming for alternative high school youth: A Review. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/josh. 12200/abstract

Tucker, J., Haye, Kennedy, D., Horta, M., Green, H., & Pollard, M. (2013). Peer influence and selection processes in adolescent smoking behavior: A comparative study. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22944605

U.S. Department of Education (2013). Friendships — Helping your child through early adolescence. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/parents/academic/ help/adolescence/part9.html

Wakefield, M., White, M., Durkin, J. & Coomber, K. (2015). What is the role of tobacco control advertising intensity and duration in reducing adolescent smoking prevalence? Findings from 16 years of tobacco control mass media advertising in Australia. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23988860

Wiium, N. & Wold, B. (2009). An ecological system approach to adolescent smoking behavior. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/publications/abstract.aspx?ID=250647

World Health Organization (2015). Tobacco. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

Appendixes

Appendix A

Search Sources

|

Database searched |

Period effectiveness searches |

| Centers for Diseases Control | 2010-2016 |

| Clinical Key | 2010-2016 |

| Cochrane Library | 2010-2016 |

| Concordia University of Nebraska Library | 2010-2016 |

| Journal articles from PubMed | 2010-2016 |

| Tobacco Control | 2010-2016 |

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | 2010-2016 |

| World Health Organization | 2010-2016 |

Appendix B

Percentage of Middle and High Students Currently Using Tobacco Products